Attaching package: 'dplyr'The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

filter, lagThe following objects are masked from 'package:base':

intersect, setdiff, setequal, unionThe real problem is that programmers have spent far too much time worrying about efficiency in the wrong places and at the wrong times; premature optimisation is the root of all evil (or at least most of it) in programming.

Donald Knuth, legendary computer scientist

In our benchmarking explorations, we jumped in and started optimising the expression we thought would have most impact.

But this is not the right way to approach optimisation and we can often end up optimising parts of our code that do not contribute much to overall efficiency.

The best way to approach optimisation is to profile our code and identify bottlenecks that need our attention before beginning any optimisation.

profvis()The best tool to perform this in R is the profvis() function in the profvis package.

Profvis is a tool for helping you to understand how R spends its time. It provides a interactive graphical interface for visualizing data from Rprof, R’s built-in tool for collecting profiling data.

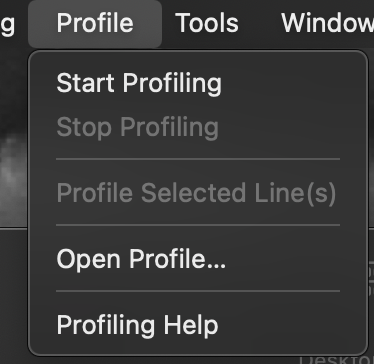

It is so fundamental that it ships with RStudio and can even be accessed directly from the IDE through the Profile menu.

Attaching package: 'dplyr'The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

filter, lagThe following objects are masked from 'package:base':

intersect, setdiff, setequal, unionLet’s use our previous example from the benchmarking section to see how we can use profvis to optimise our problem.

This example was takes from Example 2 in the profvis package documentation.

As a reminder, we’re working with a data frame that has 151 columns and 40,000 rows. One of the columns contains an ID, and the other 150 columns contain numeric values.

What we are trying to achieve is, for each numeric column, to take the mean and subtract it from the column, so that the new mean value of the column is zero.

Let’s create our data:

To profile our code, we wrap the expression we want to profile in the profvis() function. To profile multiple lines of code, we wrap the expression in {}.

profvis({

data1 <- data # Store in another variable for this run

# Get column means

means <- apply(data1[, names(data1) != "id"], 2, mean)

# Subtract mean from each column

for (i in seq_along(means)) {

data1[, names(data1) != "id"][, i] <- data1[, names(data1) != "id"][, i] - means[i]

}

})| <expr> | Memory | Time | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| profvis({ | ||||||||

| data1 <- data # Store in another variable for this run | ||||||||

| # Get column means | ||||||||

| means <- apply(data1[, names(data1) != "id"], 2, mean) | ||||||||

| # Subtract mean from each column | ||||||||

| for (i in seq_along(means)) { | ||||||||

| data1[, names(data1) != "id"][, i] <- data1[, names(data1) != "id"][, i] - means[i] | ||||||||

| } | ||||||||

| }) | ||||||||

profvis() outputThe first view in the profvis output is the flame graph view.

In the top panel we the code we profiled which includes the amount of time spent on each line of code as well as memory allocation and deallocation.

The bottom contains the flame graph. In the flame graph, the horizontal direction represents time in milliseconds, and the vertical direction represents the call stack.

Profvis is interactive!

As we mouse over the flame graph, information about each block will show in the info box.

If we mouse over a line of code, all flame graph blocks that were called from that line will be highlighted.

We can click and drag on the flame graph to pan up, down, left, right.

We can double-click on a flamegraph block to zoom the x axis the width of that block.

We can double-click on the background to zoom the x axis to its original extent.

In addition to the flame graph view, profvis provides a data view, which can be seen by clicking on the Data tab. It provides a top-down tree view of the profile. Click the code column to expand the call stack under investigation and the following columns to reason about resource allocation:

Memory: Memory allocated or deallocated (for negative numbers) for a given call stack.

Time: Time spent in milliseconds.

Back to our example, what is profvis telling us? Well the first thing it’s telling us is that we had not been optimising the slowest part of our code when we embarked on our benchmarking experiments! If anything this shows the importance of taking the time to profile properly!

Most of the time is actually spent in the apply call to generate the means vector, so, in fact, that’s the best candidate for a first pass at optimization. We can also see that the apply results in a lot of memory being allocated and deallocated.

Looking at the flame graph (or data view), we can see that apply calls as.matrix and aperm. These two functions convert the data frame to a matrix and transpose it – so much of this approach is spent on, frankly, unnecessarily transforming the data.

So let’s think of some other approaches:

An obvious alternative is to use the colMeans function. Additionally, we could also use lapply or vapply to apply the mean function over each column.

Let’s compare the speed of these four different ways of getting column means. We could use microbenchmark for a quick speed test:

microbenchmark::microbenchmark(

apply = apply(data[, names(data) != "id"], 2, mean),

colmeans = colMeans(data[, names(data) != "id"]),

lapply = lapply(data[, names(data) != "id"], mean),

vapply = vapply(data[, names(data) != "id"], mean, numeric(1)),

times = 5

)Warning in microbenchmark::microbenchmark(apply = apply(data[, names(data) != :

less accurate nanosecond times to avoid potential integer overflowsUnit: milliseconds

expr min lq mean median uq max neval cld

apply 494.1059 520.7200 536.5105 535.1372 563.3437 569.2459 5 c

colmeans 149.5276 155.7630 176.8923 170.1143 190.1017 218.9548 5 b

lapply 112.2835 113.3969 113.2311 113.3998 113.4851 113.5901 5 a

vapply 110.3491 113.4187 112.8524 113.4573 113.4850 113.5521 5 a colMeans is much faster than using apply with mean but that lapply/vapplyare faster yet.

To dig into the underlying causes we could use profvis again, profiling each of our candidate approaches.

profvis({

data1 <- data

# Four different ways of getting column means

apply(data1[, names(data1) != "id"], 2, mean)

colMeans(data1[, names(data1) != "id"])

lapply(data1[, names(data1) != "id"], mean)

vapply(data1[, names(data1) != "id"], mean, numeric(1))

})| <expr> | Memory | Time | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| profvis({ | ||||||||

| data1 <- data | ||||||||

| # Four different ways of getting column means | ||||||||

| apply(data1[, names(data1) != "id"], 2, mean) | ||||||||

| colMeans(data1[, names(data1) != "id"]) | ||||||||

| lapply(data1[, names(data1) != "id"], mean) | ||||||||

| vapply(data1[, names(data1) != "id"], mean, numeric(1)) | ||||||||

| }) | ||||||||

Now we see that colMeans is still using as.matrix, which takes a good chunk of time while the lapply and vapply primarily spend their time calling mean.default.

lapply returns the values in a list, while vapply returns the values in a numeric vector, which is the form that we want, so it looks like vapply is the way to go for this part.

So let’s edit our code, replacing apply with vapply and try again:

profvis({

data1 <- data

means <- vapply(data1[, names(data1) != "id"], mean, numeric(1))

for (i in seq_along(means)) {

data1[, names(data1) != "id"][, i] <- data1[, names(data1) != "id"][, i] - means[i]

}

})| <expr> | Memory | Time | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| profvis({ | ||||||||

| data1 <- data | ||||||||

| means <- vapply(data1[, names(data1) != "id"], mean, numeric(1)) | ||||||||

| for (i in seq_along(means)) { | ||||||||

| data1[, names(data1) != "id"][, i] <- data1[, names(data1) != "id"][, i] - means[i] | ||||||||

| } | ||||||||

| }) | ||||||||

Our code is about 3x faster than the original version. Most of the time is now spent on line 6, and the majority of that is in the [<-.data.frame function. This is usually called with syntax x[i, j] <- y, which is equivalent to `[<-`(x, i, j, y). In addition to being slow, the code is ugly: on each side of the assignment operator we’re indexing into data1 twice with [.

profvis({

data1 <- data

means <- vapply(data1[, names(data1) != "id"], mean, numeric(1))

data1[, names(data1) != "id"] <- purrr::map2(

data1[, names(data1) != "id"],

means,

~.x - .y)

})| <expr> | Memory | Time | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| profvis({ | ||||||||

| data1 <- data | ||||||||

| means <- vapply(data1[, names(data1) != "id"], mean, numeric(1)) | ||||||||

| data1[, names(data1) != "id"] <- purrr::map2( | ||||||||

| data1[, names(data1) != "id"], | ||||||||

| means, | ||||||||

| ~.x - .y) | ||||||||

| }) | ||||||||

In this case, it’s useful to take a step back and think about the broader problem. We want to normalize each column. Couldn’t we we apply a function over the columns that does both steps, taking the mean and subtracting it? Because a data frame is a list, and we want to assign a list of values into the data frame, we’ll need to use lapply.

profvis({

data1 <- data

# Given a column, normalize values and return them

col_norm <- function(col) {

col - mean(col)

}

# Apply the normalizer function over all columns except id

data1[, names(data1) != "id"] <- purrr::map_dfc(

data1[, names(data1) != "id"],

col_norm)

})| <expr> | Memory | Time | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| profvis({ | ||||||||

| data1 <- data | ||||||||

| # Given a column, normalize values and return them | ||||||||

| col_norm <- function(col) { | ||||||||

| col - mean(col) | ||||||||

| } | ||||||||

| # Apply the normalizer function over all columns except id | ||||||||

| data1[, names(data1) != "id"] <- purrr::map_dfc( | ||||||||

| data1[, names(data1) != "id"], | ||||||||

| col_norm) | ||||||||

| }) | ||||||||

profvis({

data1 <- data

# Given a column, normalize values and return them

col_norm <- function(col) {

col - mean(col)

}

# Apply the normalizer function over all columns except id

data1[, names(data1) != "id"] <- lapply(data1[, names(data1) != "id"],

col_norm)

})| <expr> | Memory | Time | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| profvis({ | ||||||||

| data1 <- data | ||||||||

| # Given a column, normalize values and return them | ||||||||

| col_norm <- function(col) { | ||||||||

| col - mean(col) | ||||||||

| } | ||||||||

| # Apply the normalizer function over all columns except id | ||||||||

| data1[, names(data1) != "id"] <- lapply(data1[, names(data1) != "id"], | ||||||||

| col_norm) | ||||||||

| }) | ||||||||

Now we have code that’s not only about 6x faster than our original – it’s shorter and more elegant as well. Not bad! The profiler data helped us to identify performance bottlenecks, and understanding of the underlying data structures allowed us to approach the problem in a more efficient way.

Could we further optimize the code? It seems unlikely, given that all the time is spent in functions that are implemented in C (mean and -). That doesn’t necessarily mean that there’s no room for improvement, but this is a good place to move on to the next example.

Rprof()I just wanted to mention that profvis effectively wraps utils functions Rprof() and Rprofmem() that ship with R for profiling execution times and memory allocation.

Should your code generate a really complicated call stack that is hard to weed through with profvis(), you could try Rprof() (which writes it’s results to a file, here a temporary file) followed by summaryRprof() to drill down to the function calls that are taking the most time:

prof_file <- tempfile()

Rprof(prof_file)

data1 <- data # Store in another variable for this run

# Get column means

means <- apply(data1[, names(data1) != "id"], 2, mean)

# Subtract mean from each column

for (i in seq_along(means)) {

data1[, names(data1) != "id"][, i] <- data1[, names(data1) != "id"][, i] - means[i]

}

Rprof(NULL)

summaryRprof(prof_file)